International Women's Day - Women who Paved the Way

Like so many areas of study, women have been the silent heroes of STEM, dating back as far as “HERstory” itself. Every day we celebrate the women behind Wild Interiors and are extremely lucky to have their expertise, knowledge, and care working with our plants every day. In an industry that like so many has been male-dominated in the past, the field of horticulture has been no different, but things are changing…

“As a woman, it can absolutely be tough working in this field. The greenhouse can be a busy, demanding place, especially during peak seasons. But at the end of the day, I have such a passion for what I do that I wouldn't change a thing. “

-Ashleigh Gomez, Section Grower & Chemical Consultant

With so many accomplished women working for Wild Interiors and the horticulture industry today, we look to the past to acknowledge and thank the women that came before us for paving the way. Janaki Ammal and Jane Colden are two women who are generally not among household names. Their contributions to the botanical world, however unsung, continue to be felt today. Let’s meet these ladies and sing their praises as we celebrate International Women’s Day!

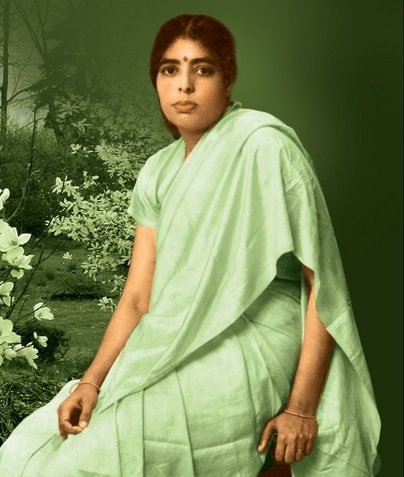

Janaki Ammal - the Sweetest Botanist

(1897-1984)

Source: Wikimedia

Considered “India’s First Female Botanist,” Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal was born in the Indian state of Kerala in 1897. From an early age, Janaki broke the mold and pursued education in a time when most women in India were illiterate. She studied in the United States, attending the University of Michigan and earning a doctorate in Botany, making her the first Indian woman to do so in the U.S!

So how did Janaki apply all she learned to make “HERstory”? Her research in genetics and breeding helped to develop sustainable hybrid sugarcane varieties that allowed India to become independent from sugarcane imports. She co-authored what would become an important reference for plant scientists today, the Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants, which looked to chromosomes for plant classification rather than traditional botanical characteristics. This was a pivotal moment in plant science, and the reclassification of plants based on genetics is still happening today.

When she returned to India in the 1950s, Janaki began her most environmentally important work. After years of working with plants in a commercial sense, she pivoted toward limiting the effects of deforestation and protecting native plants. She found herself going toe-to-toe with the imperialism that had allowed her to study plants on the other side of the world. Janaki understood the importance of indigenous knowledge in the preservation of biodiversity in a time when imperialists drove so much of the research. Her involvement in the Save Silent Valley environmental movement ultimately led the Indian government to abandon a hydroelectric dam project that would have wiped out the Silent Valley forests. (You may note that Janaki’s name is not immediately found when looking into this movement.) She did not live to see this victory, as she passed away in 1984 at the age of 87.

Janaki Ammal’s name is not well known in her own country, but her impact can be seen through the preservation of lands that would eventually become a national park. Her work in cytology led to the creation of the Magnolia kobus ‘Janaki Ammal’, and a hybrid yellow rose variety has been named after her. She fought against classism, racism, and sexism to impact the world of Botany. With that, she helped to make the world a little sweeter, and we are not just talking about her sugarcane varieties!

Jane Colden - an American First

(1724-1766)

Source: Scenic Hudson

America’s first female botanist made her mark before some of the country’s founding fathers even arrived on its shores. Born in colonial New York in 1724, Jane Colden was the daughter of a physician turned politician Cadwallader Colden. Cadwallader, a botanical scholar himself, was the first to apply the newest form of classifying plants to never before identified American flora. This Linnaean Classification System was developed just a few years earlier by Swedish botanist Carl Linneaus. Her father passed on his passion for botany and natural sciences to Jane as she was raised and educated at home. Soon, her skills in Linnaean taxonomy - in identifying, classifying, and documenting plants - overshadowed her father’s! By 1758, Jane had classified over 400 species of plants from the lower Hudson River valley. Her skill in drawing plants was unmatched, and she even developed her own technique for making ink leaf impressions. Alongside her drawings and descriptions, Jane further documented medicinal and nutritional uses of flora, relying on her relationship with local Native American tribes. She discovered several species of plants but was denied the right to name them.

Jane married in 1959, and she died seven years later at the age of 41 during childbirth. Her manuscript would not come to the attention of Americans for another 75 years. Despite her unprecedented work, Jane was still just a woman living in the 18th century, and her name faded into history. There are some who say that had she been a man, she would have been noted as one of the foremost botanists of American history.

Janaki Ammal and Jane Colden are just two examples of strong, educated women in history whose names some would say are relatively lost to history. Many women have dedicated their lives to the betterment of our natural world. Often in history, women even risked their own lives to do the work they love, pushing against societal norms and obligations. Even today, women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) face gender bias and are underrepresented in most STEM-related fields. What is more, women of color have even less representation and opportunity.

So today, on International Women’s Day, we salute Janaki and Jane and their contributions to the world of plants! May we all take some time to tend to our plant babies and think of all the Crazy Plant Ladies of history who have paved the way for women today.

Sources: the Smithsonian, Scientific Women, Scenic Hudson, and Sierra College.